Finding the Familiar in Far-Off Madagascar

If it were possible to insert a rod from my home straight through the exact center of the earth, the place it would emerge would be the Indian Ocean off the coast of Madagascar In my travels, I often seek out the destinations that will bring me the farthest mentally, physically, and culturally from my everyday suburban life on the west coast of the United States. So, when I had the opportunity to spend a week in the far-off, nearly mythical island nation of Madagascar, the allure was immediate and undeniable. Traveling there I hoped to glimpse an elemental, pure way of life and to see the results of an ecosystem isolated and left to its evolutionary devices for 80 million years. This would literally be the farthest I could travel without leaving the planet.

Not long into my local tour, I was driving in southwestern Madagascar from Isalo National Park to Toliara along the sole two-lane road that makes automobile travel possible here. Most of the landscape was raw, red, and deforested, but in the protected area of Isalo National Park, I had seen charismatic ring-tailed lemurs leaping among branches, spied chameleons with protruding eyes peering 360 degrees around them, and scrambled along the bottoms of winding, steep-sided riverine canyons to pristine swimming holes that offer hikers some respite from the heat and humidity that encase this land. In short, I had seen what I had hoped to see in Madagascar’s most visited national park. But as I traveled this road, I was rewarded with something far greater than lemurs and rock formations.

To break up the five-hour, 150-mile drive to Toliara, I stopped at a small lodge just west of the Zombitse-Vohibasia National Park, another island of protected green forest, to stretch my legs and take a moment to drink a bottle of the local, extremely sweet soda. As I refreshed myself, a group of eight children from the neighboring village came to investigate this new face in their midst. Their village, like many I had passed on my journey, consisted of perhaps a dozen homes constructed solely of wooden sticks and branches, thatch, and mud. No school, no health clinic, no more substantial building other than the lodge existed for many miles in any direction.

I greeted them with one of the two words of Malagasy I had mastered, “Salama!” When they heard their native tongue emerge from this unexpected place, their faces opened into dazzling smiles. “Salama!” came the returning chorus, accompanied by an audible waterfall of giggles. But after these initial greetings, our conversation was stymied by a lack of common vocabulary.

Out of the space between us, still filled with giggles and smiles, one girl dressed in a simple pink dress with her hair in braids, shyly said, “Bonjour.” Aha! I had forgotten that, since Madagascar had been a French colony from 1897 until 1960, French is still the second official language here. Happily, while my Malagasy was limited to two words, my French, thanks to high school studies many years ago, was somewhat more extensive, though calling it rusty would be generous.

“Vous parlez francais?” I asked. My pronunciation was terrible, and I probably had used the wrong form of address, but it didn’t matter.

“Oui, oui.”

“C’est votre village?”

“Oui.”

“Je m’appelle Stephanie.”

“Je m’appelle Aina” (or so it sounded).

We were off to a roaring start and for possibly the first time in my life, I wasn’t embarrassed by the inept nature of my French. The other children in the group chimed in and we “discussed” the familial relations between them, including who was siblings with whom and who were just friends and how old they all were (between two and fourteen years old).

Wanting to immortalize this moment for myself, I looked for my camera, but realized I had left it in the car. In my backpack, however, was my large iPad Pro, and I reached for it to take a photo. The children’s eyes grew wide as this technological marvel emerged. I accessed the camera, knelt to take a couple of quick photos of the group, then showed the children their own images on this bright, clear, colorful 11-inch screen. They responded first with startled gasps and then giggles and excited, rapid-fire conversations in Malagasy.

To capture these exuberant reactions on video, I activated the tablet’s forward-facing video function and pressed the record button, and the children’s moving images appeared on the screen in front of them. At first, they couldn’t quite understand what they were looking at, but a moment later brought more squeals of delight as they craned their necks to one side and then the other to examine themselves in full living, digital color.

Finally, I reluctantly said goodbye to the children, as I had to continue my Madagascar local tour. Part of me yearned for the days of the Polaroid when I could have left photos of them there, so they could have a tangible remembrance of the encounter. I, however, had a priceless and indelible souvenir in the form of a video of their giggles of delight and radiant smiles. I marveled that the iPad, which I had not thought of as a means of connection, had made communication with the Malagasy possible, and I wondered how else I might be able to use this technological marvel to connect with other Malagasy.

Two days later, I found myself walking the main thoroughfare of the coastal town of Andavadoaka, a small fishing village about one hundred miles north of Toliara. As I walked the sandy road, bordered by simple houses constructed of all manner of materials, including thatch, lumber, stone, sticks, and clay, I drew many stares and smiles. Greeting the locals again and again with “Salama” elicited the same response back to me accompanied by the wide, unreserved smiles I had begun to associate with these people.

I also attracted a good number of children who had apparently decided that walking this road with me was the most interesting thing going on in Andavadoaka that morning. As we ambled through the town, we conversed sporadically in our halting French. We walked together first past the local Methodist church, where the services were still going on and glorious voices joined in song emanated from its thin wooden walls. After we had passed the town well, the marketplace, many dwellings, and two Catholic schools, I decided to see if I could engage these children with the tablet once again. I took a few photos and videos of them and they laughed and marveled at seeing themselves on the big screen in high resolution and bright color.

One of the children was a shy girl about ten years old in a dark brown corduroy dress with a bright pink belt around her waist. She had been walking near me all morning, smiling shyly the whole time, but had never gotten too close. I decided to see if I could engage her a bit more, so I knelt and beckoned her to come over.

“Salama,” I said to her.

“Salama,” she answered in barely more than a whisper.

I showed her the tablet and navigated to the drawing function of the notepad. Using my finger, I drew a very simple smiley face. Then a few more squiggles. I cleared the screen and gestured to her to try. She gave a small smile and nodded. After carefully wiping her index finger on her dress, she very tentatively touched the screen and made a small mark. Then a wash of familiarity came over her face and a look of focus and concentration. Very slowly and deliberately, in careful handwriting, she began to write numbers in precise vertical columns. When the screen was filled, I cleared it and she continued to fill another screen and then another with more vertical columns of numbers.

By this time quite a scrum of children had gathered around the two of us. A few other children wanted to try, and they all did the same thing. No pictures or scribbles, just columns and columns of carefully written numbers. I showed them a few times that they could use different colors or draw designs, but they all wanted to continue with their scholarly numbers. After a while, it was time for me to move on and the crowd of children walked me back to the beach. The girl in the brown corduroy dress held my hand the whole way.

A few days later into my Madagascar local tour, I found myself on one of the “Barren Islands” about 20 miles off the west coast of the country in the Mozambique Channel. These spits of land are not quite entirely barren but are occupied by small communities of fishermen and their families who stay for a few months at a time, fishing and drying their catches before bringing them to the mainland to sell. There are practically no structures of any kind of permanence. These families were living in tents made of thatch under the meager shade of some sparse trees. The sun pounded down relentlessly on their beautiful white sand beach, but the crystal-clear blue water here was a place for work, not recreation. About 60 people in all currently made this small island their home.

They, like all of the Malagasy people I had encountered, met me with a mixture of friendliness and curiosity. As I walked around their tiny settlement, I encountered women making a breakfast porridge of rice and fish, men working on fishing canoes and nets, and children playing with anything they could find. There was also a group of men and women working to turn over and sort a huge number of cleaned fish drying in the sun on thatch racks.

After a while, some of them moved under a large white piece of fabric strung between tall wooden poles to create a kind of communal shade structure. This group, mostly young men whose ages I would estimate between 15 and 25 with a few village elders probably over 45, motioned for me to join them. I sat down in the powdery white sand and attempted to speak French with them, but they knew very little.

Thinking back to my previous encounters, I once again pulled my trusty iPad from my backpack. Once again, I took their photos and videos, and this time they were not a bit shy, laughing uproariously and posing and dancing for the camera, delighted with the results. Then I navigated to the drawing function of the notepad program and showed them how to use it with their fingers, changing colors and thickness of the line, drawing my simple stick figures and smiley faces. They caught on almost immediately, though one of them did touch the place on the screen where you choose colors, looked on his finger and frowned, and touched the place again harder, apparently trying to make the color adhere to his finger.

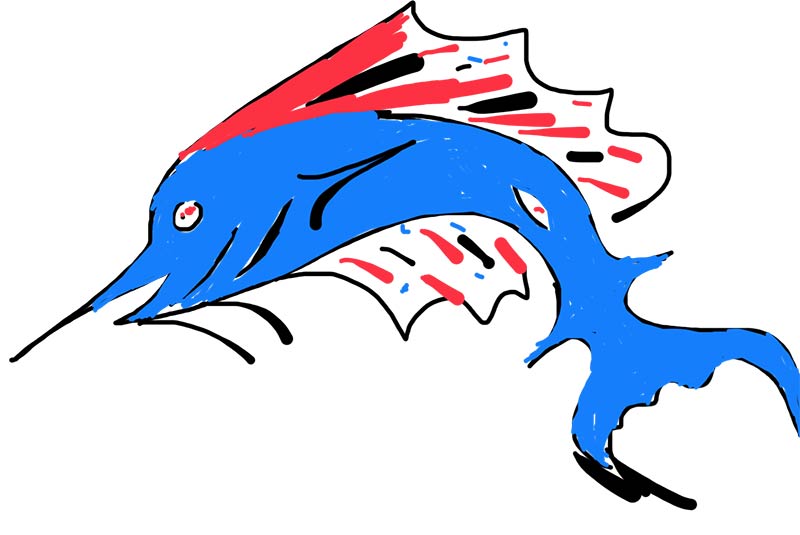

Very soon, the oldest man in the group came over and told the younger men to move aside. He sat down on the sand in front of me and very deliberately started drawing with short delicate strokes. He sketched with a great deal of focus and intensity, seemingly not wanting to make any false moves. Occasionally, one of the younger men would say something to him and he would quiet them with a hand gesture. Gradually, a beautiful drawing of a shark appeared on my screen. When he was done, he looked up at me with a glowing smile and I showed his drawing to the group, which shouted its appreciation. Clearing the screen, he then proceeded to draw lifelike successive representations of a turtle, a swordfish, and another species of fish I didn’t recognize, to more praise from the assembled group.

Eventually, a younger man of about 22, who I learned was named Zachary, asked to try, and the older man relinquished his spot. As the rest of the group looked on, Zachary proceeded to focus with equal intensity as sweat beaded on his forehead. He had a grasp of using the various colors and tools of the device that his elder had lacked, and after a while, he produced stunning, detailed drawings of a swordfish in red, blue, and black, and a dolphin in black, blue, yellow, and red. With no apparent access to writing implements or paper, I found it astounding that they had nurtured such artistic talent and could produce such beautiful renderings of the sea creatures they know so well. When it came time for me to leave this unique little island community later that morning and as this group of men went back to their work, my only regret was that I couldn’t somehow print out or email these works of art that Zachary and his elder had produced.

On my journey home, as I always do, I looked back at the photos of what I had experienced. I had beautiful images of the Madagascar landscape, the wondrous animals I had seen, towering and majestic stands of baobab trees, and fascinating street scenes from the towns and villages I had visited. But I found that my most cherished remembrances were the videos of those first children along the road to Toliara, those careful rows of numbers printed by the girl in the brown dress, and the drawings of sea life by the fishermen of the Barren Islands. Unexpectedly, with a bit of the technology that so permeates my world at home, I had been able to open a portal to fleeting and precious interactions. I may have traveled to the farthest spot possible on the planet seeking wildlife and adventure, but the most important things I found there were moments of connection that showed and celebrated our shared humanity.

# # # # #

To find out about the many ways to explore Madagascar, or any other of our far-flung destinations, give us a call at 888-570-7108.